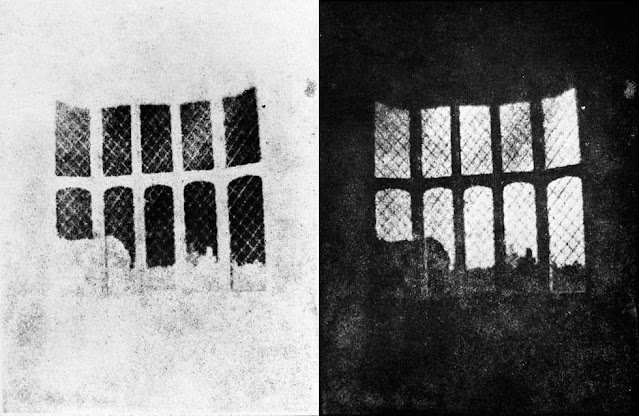

Christians go to Bethlehem, Muslims go to Mecca and ABBA fans go to Stockholm. Photographers on the other hand go to Lacock Abbey. Unless you're French but we'll come to that and you'll be entirely justified. The image you see above, if you're reading this blog, is one you've probably seen and if you haven't, this is going to get you very excited. Its one of the word's first photographs taken all the way back in 1835 by a certain Henry Fox Talbot, erstwhile Liberal MP, scholar, inventor and visionary - quite literally. Some say he created the world's first 'modern' photo or 'practical' photo. Why modern or practical? Because it was the first image, using a system that involved the use of a photographic negative from which as many positive prints as you want could be created allowing not just the sharing of pictures with friends and family, but publication in books and magazines. This was pretty revolutionary, as he went to demonstrate in his book The Pencil of Nature, which contains 14 photographs showing for the first time his pictures of things and places with which he sought to demonstrate his invention. For us, its a book with photos. For the early Victorian public it must have been nothing short of startling. They would have never seen a book like this. In a time when inventions were coming thick and fast this would nonetheless have been the stuff of headlines, and indeed it was because argument and strife was afoot regarding photography and who could take credit for its invention.

Our friends in France are justifiably outraged by this claim to the first photo because the splendidly named Nicéphore Niépce had nearly a decade on our friend Mr Fox Talbot, producing an image of the rooftops seem from his window in La Gras. In fact, this image wasn't the first produced as he'd been experimenting with a way of capturing impressions on light sensitive material for some time, but this is thought to be the first recording of a photo as we might recognise it. Modern research using his notes to recreate the experiment which led to the image has found that the sensitivity of the historically correct materials (a bitumen based recipe coated onto a pewter plate) was so low that it took an exposure of several days to create the image. Niépce's pictures however were all one off's and were unique in that they couldn't be copied. However the technology developed quickly, evolving into the Daguerreotypes we're familiar with today which soon got to the point where they produced clear and detailed images. So which was the first image modern photo? You decide. They were both marvels of their age and important stepping stones that allowed both the science and the art of photography to flourish. The Niépce picture, like the Fox Talbot one, survives and is reproduced below.

Last week I found myself not in Bethlehem, Mecca or Stockholm, but Lacock Abbey which these days is in the hands of the National Trust who preserve it for the nation as they do so many other stately homes. In an annexe you'll find a museum devoted to Henry Fox Talbot and the discovery and subsequent development of photography. Its a grand old house to be sure, and photogenic in its own way. Its a bit of a photographers dream really as the village of Lacock itself is a typical chocolate box Cotswolds affair and the Abbey is an easy walk through the charming streets though you might not make it before closing time because there's so much to stop and photograph along the way, not to mention a couple of ancient pubs to tempt the unwary. If there's any negative (see what I did there?) its that its an awkward chug for non-drivers to get there. The bus service is infrequent and if you're not coming from Chippenham you're out of luck. So arrange your journey very carefully with the timetables, or share a taxi. The distances aren't great but taxis aren't cheap either.

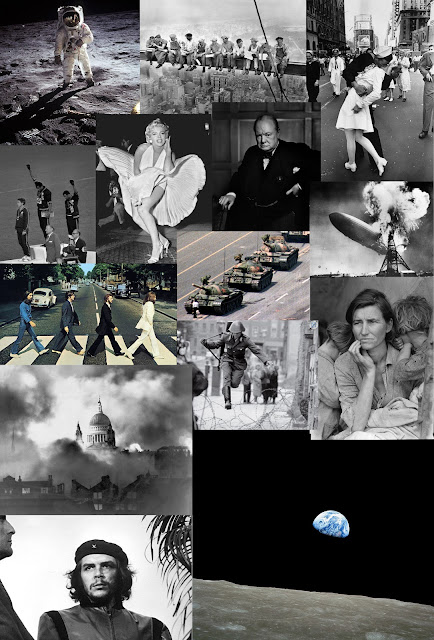

Passing through the entrance and seeing the Abbey across the field was a bit of an emotional moment actually. Photography has been a big thing all my life, and it started here (ok and in La Gras but you get my point, I was having a moment). The first surprise was the window. I'd always imagined this mighty window being in some great room but no, we're having none of if. Its on a minor corridor leading off from a moderate sized room. No-one else was there so I had the window to myself. How many others have stood there and got a little lost in thought? Every photo that ever was owes something to this window and the effort it took to expose this tiny postage stamp sized image onto a negative. Think of all the iconic images we've seen; the mushroom cloud over Hiroshima, Marilyn Monroe's white dress over the air vent in New York City, the Hindenburg collapsing in flames, Neil Armstrong standing on the Moon and Nelson Mandela walking to freedom at the end of apartheid in South Africa. They all started with this window.

The rest of the Abbey is interesting enough, as you would expect. Like all National Trust properties it's impeccably presented with volunteer guides in key rooms to explain the history to you. The house was built in the 16th century around the earlier 13th century Abbey which was abandoned following the dissolution of the monasteries in Tudor times. The medieval cloisters remain though the church has long since gone. Additions have been made over the centuries so its a bit of a mish-mash of styles, though the Tudor elements are very clear walking around. Like the impossibly pretty Lacock itself, the Abbey was used for location filming on some of the Harry Potter films, in particular the cloisters. When I was there some Japanese Potter fans were selfie'ing the bejaysus out of the cloisters, complete with Hogwarts gowns. It rather makes you wish photography hadn't been invented sometimes but then I wouldn't have been there either I suppose 😕

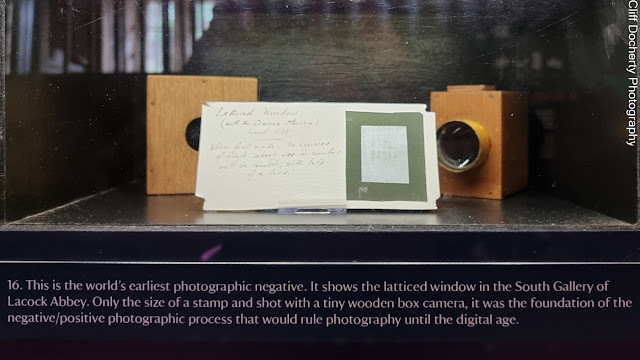

Outside, the grounds are extensive with a pretty enough walled garden with plants for sale, but I was more interested in the Fox Talbot Museum. Devoted to photography it's small but beautifully formed with an upper gallery for a constantly changing programme of exhibitions inspired by his work and techniques. Inside you will find a pretty comprehensive selection of early cameras and films, and examples of what they produced, but the star of the show is a copy of his window picture and the 'camera obscura' he used to capture the image. What's breathtaking is just how tiny the image is. Little more than a postage stamp coated with light sensitive chemicals, it seems so innocuous but it changed the world. He struggled for a long time to find a way to fix the image and there was a war being fought for a long time over who should get the kudos. What's clear is that a lot of people were working on the same idea, with different approaches. The Niépce/Deguerre process probably won on quality in the initial years but ultimately it was Fox Talbot's idea of a negative/positive process that was seen as the way forward, eventually evolving into a film based medium. The Daguerreotype was a relatively short-lived process.

Looking at those little wooden boxes that Fox Talbot used, its a reminder that today we use much the same thing in pinhole photography. He went on to create pictures of great sensitivity with these simple cameras. The picture of his servant Nicholas Henneman taken just a few years after the initial shot of his window is touching and strangely moving. By this point he had refined the process to needing only a few seconds for exposure. The original photo is at the British Library and it can be viewed here. You don't need to go to the depths of Somerset to see these cameras though, The Victoria and Albert Museum has several of these very precious items in their collection in London and they can be seen at their new Photography Centre.

In the century and a half since that picture of Fox Talbot's window was taken the world has changed beyond all recognition and we've moved away from negatives, though we still use film for photography and motion pictures. It remains a niche interest which has seen a resurgence of interest after never really dying out when digital came along. The reasons why are discussed at length in countless blogs and articles in print and online, but as we move more and more into a virtual, instant and AI world, it seems more and more of us crave the tactile experience of the creative process. As much as there will always be a demand for speed and expediency, there will always be a need for people to feel they can make things, express themselves and process something, mentally as well as physically, because from that you get the satisfaction, the learning and feeling of growth.

I doubt I'll ever take an iconic photo but when I do take a photo now and then I get a result where I feel, yeah, that's nice. I'm pleased with that. It says something. As the world changes faster and faster it seems more and more important to freeze it so we remember how it was.

Comments

Post a Comment